At Brooklyn College, artists of color, both faculty and alumni, have throughout their careers continued to address social issues such as race, identity, migration, gentrification, and history (and who owns it). These same artists—professors Derrick Adams and Eto Otitgbe, Nari Ward ’92 M.F.A., and Chloë Bass ’11 M.F.A.—have seen the art scene open up to include those who have embraced the use of multimedia, and reimagined how people of color, particularly Black people, should be seen.

In our recent conversation with the artists, they spoke about the definition of Black art, art stewardship and inclusivity, teaching, and the artist’s role in public spaces. Their thoughts on these topics and their hopes for future generations of artists follow.

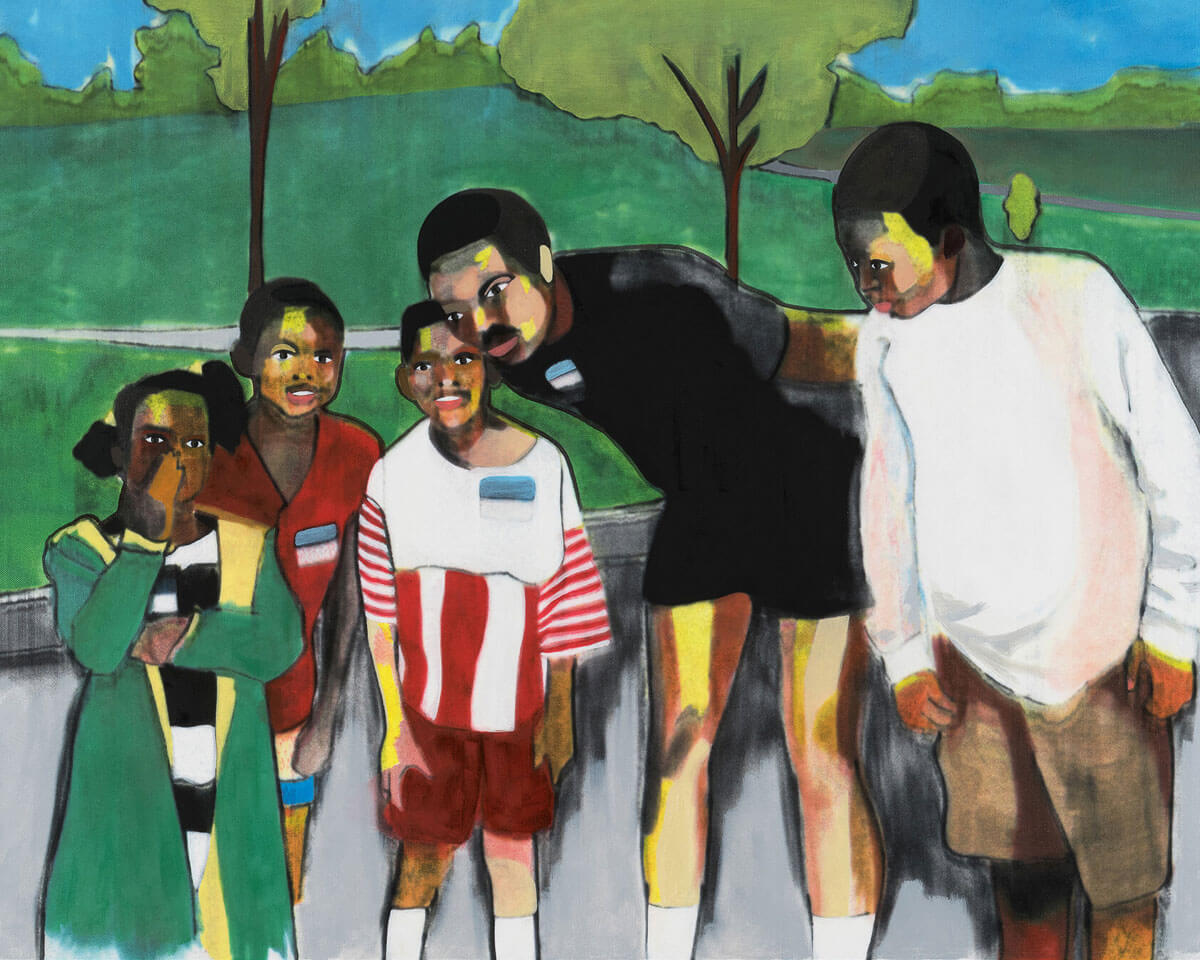

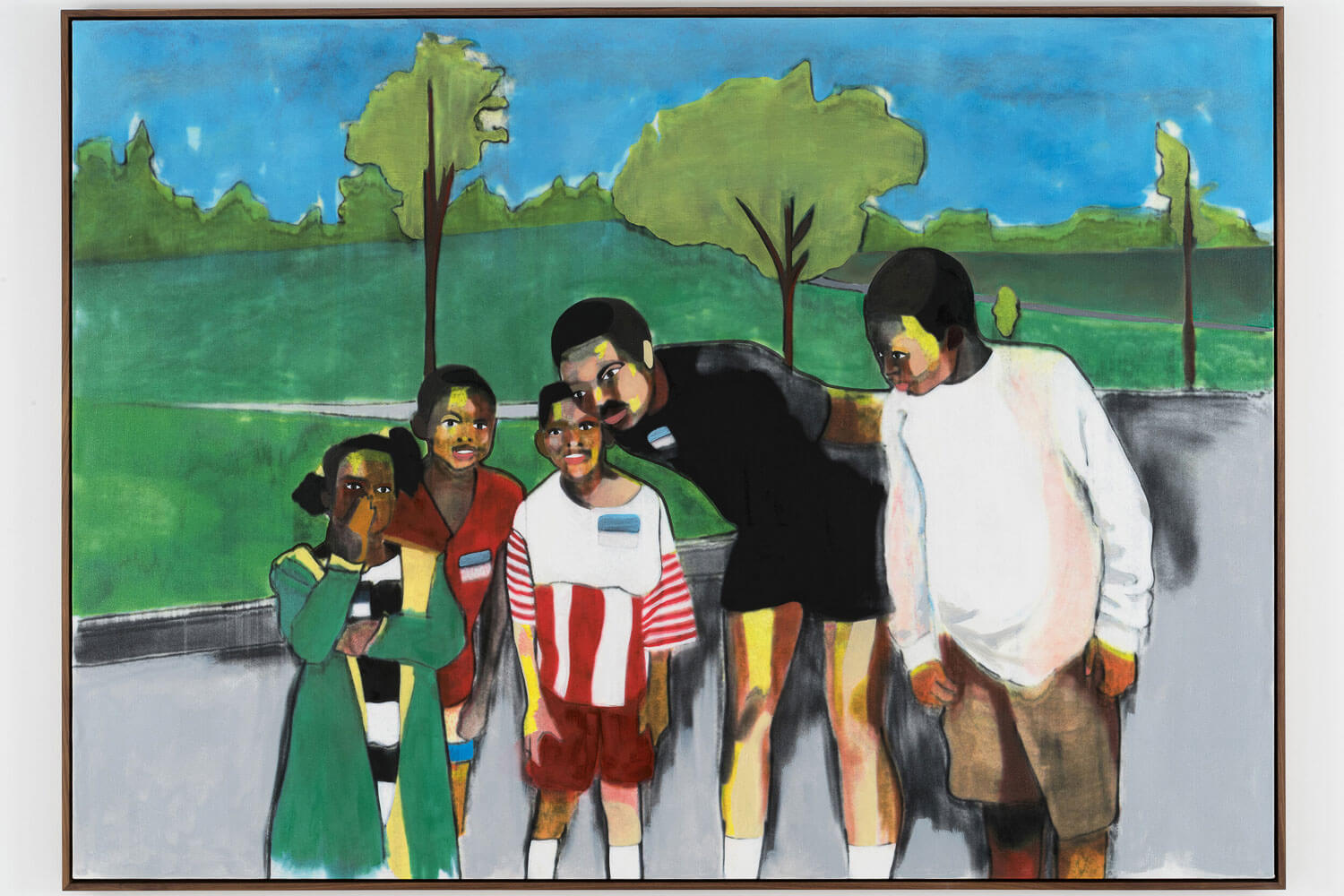

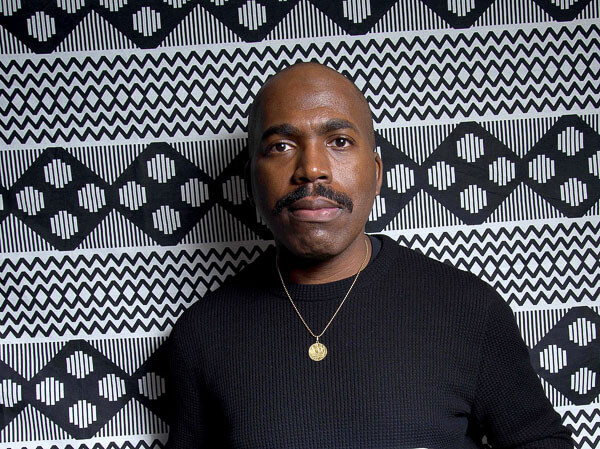

Derrick Adams, Assistant Professor of Art

Derrick Adams

“We, as creatives of color, have been responsive to making work that highlights trauma; work that focuses on the sympathetic nature of “the other”—us—for the viewer. This art looks at us and pulls the empathy right out of people. We need a visual break,” says Derrick Adams about the long tradition of the portrayal of Black trauma through images. It’s Adams’ mandate to bring balance to the overwhelmingly dispiriting picture of Black misery that has haunted the mainstream cultural and historical canon.

Adams’ series Buoyant, late of the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, Florida, is restorative. In bright, bold colors, Adams paints a world of Black people relaxing in pools, celebrating at parties. The message is these are people of color living their best lives.

“Buoyant came out of my wondering if there were any images of civil rights activists like Martin Luther King on vacation. I found an Ebony spread of Martin and Coretta in Jamaica, enjoying themselves in a pool,” says Adams.

“There is never going to be a shortage of trauma. There are artists who have that area covered,” says Adams. “We need a balance for us to open the narrative and talk about the complexity of the Black figure. The definition of a human being is a person who experiences multiple emotions. We exist beyond the imposed narrative of oppression. I’m always thinking about how to engage in those concepts of endurance, perseverance, joy, normalcy. The broader narrative that will fuel a new generation who will benefit our culture in a big way.”

Adams joined the Brooklyn College faculty in 2017 after earning a B.F.A. from Pratt Institute in 1996 and an M.F.A. from Columbia University in 2003. He is also an alumnus of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture artists residency in Madison, Maine (as are William T. Williams and Nari Ward). He is the recipient of several honors, including a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency, a Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship, and a Studio Museum Joyce Alexander Wein Artist Prize. He has had numerous solo shows, including Where I’m From—Derrick Adams (2019) at The Gallery in Baltimore City Hall; Derrick Adams: Sanctuary (2018) at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York; and Derrick Adams: Transmission (2018) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver. His work has been a part of public exhibitions such as Men of Change: Power. Triumph. Truth. (2019) at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati; PERFORMA (2015, 2013, and 2005); The Shadows Took Shape (2014); and Radical Presence (2013–14) at The Studio Museum in Harlem (2012).

Teaching in the Brooklyn College B.F.A. program has been enriching and rewarding for Adams.

“I like educating people and being educated by my students. At one point, I said to myself, with all of the education that I gained, I’d be a more effective teacher in a school with more diversity and a bigger population of Black students,” he says. “I was teaching at private institutions and my career took off enough so I didn’t have to teach anymore. I told friends that the only way I’d teach again was if someone called me from a city college and offered me a job. Six months later, it happened.”

“I’m getting such a reward. Many of my students are first-generation and have so many interesting stories to tell from their cultures. They all bring content with them. My job is to help them to be performatively excellent, make their work from the narrative they are being inspired by. In other schools it’s often the other way around—they are formally trained but have no content.”

Adams says that sometimes the biggest hurdle for his students is their family. Meeting them at open studios helps to convince parents of color of the significance of art. “My being there as an African-American artist has helped give agency and reassurance to Black parents and parents of color. We need more representation in the arts to show we’ve been doing this.”

Eto Otitigbe, Assistant Professor of Art

Eto Otitigbe. Photo by Tahir Karmali

Assistant Professor Eto Otitigbe believes in using art in what he calls “live interventions.” Invited to the University of Texas at Austin by Cherise Smith, director of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies. to participate in a residency that would culminate in an exhibition in a newly established gallery, he took in the beautiful campus with its extensive art collection. He was stopped short when he walked the grounds. “There I was in this vast green space, surrounded by Confederate statues. My response was to feel threatened and ask why such racist icons should exist at an institute of higher learning?” This question anchored his investigation into the history of Confederate monuments and statues and became the exhibit Patience on a Monument, which showed in 2016 at what is now the Christian-Green Gallery at the university.

“Along with videos and sculpture, I invited University of South Carolina professors Thaddeus Davis and Tanya Wideman, who are co-directors of Wideman/Davis Dance to reinterpret the landscape using choreography,” says Otitigbe. “We wanted to perform activations around those Confederate monuments, but were told that, no, we couldn’t do that. Instead, we participated in a `Racial Geographies Tour‘ of UT Austin led by Professor Ted Gordon and conducted an impromptu performance during the tour in what was more of a disruption. We were using choreography to express a perspective on a difficult issue.”

Otitigbe’s dedication to working with and transforming public spaces into loci of discourse, dialogue, and engagement was spurred by Myron Beasley, his professor at the Transart Institute at the University of Plymouth in England, where he completed his M.F.A. in creative practice in 2012.

Beasley curated Patience on a Monument. In the introduction to the exhibition, Beasley writes, “Monuments are said to help us commemorate, celebrate and edify a memory, a history. Patience on a Monument gracefully disrupts the monolithic history that public art, monuments in particular, has come to represent. Instead, assembled here in this show are objects that play with the concept of public art and participate in an ongoing dialogue about the precarious domain of public memory.”

Repair Work

As the artist dug deeper into his research (the book Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves by Kirk Savage played a significant role), he found that the people who championed statues like those of Confederate heroes were a small group with a very specific and political interest in who remained in power. “But they did not represent the majority of their fellow community members,” says Otitigbe.

“When objects are made of stone and elevated, the power of architecture and geometry does not encourage us to question their existence. Questions surrounding the trauma they may enact on folks of different backgrounds are left unasked and unexamined.”

In Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, one of the goals set by the memorial design team was to acknowledge and honor the enslaved people who worked at the university. “The enslaved people were denied personhood, and as a result their descendants, some who still live in and around Charlottesville, were denied an opportunity to honor and memorialize them.”

“Mabel Wilson, a historian on the memorial design team, refers to the project as ‘repair work.’ That memorial is indeed a repair,” Otitigbe says. And instead of a looming presence, the memorial remains low to the ground and is shaped like a catch basin, “the reverse of Jefferson’s Rotunda at UVA.”

“UVA has expressed profound regret over its history of slavery; the memorial is a public expression of that regret,” says Otitigbe. “Conversations around this topic can be fraught, tense. We worked to create a space for healing, or protest, a space where change can always be facilitated.”

Otitigbe’s multimedia works draw the people who view them to the intersection of race, history, and politics, from his 2013 outdoor sculpture Looping Back in Randall’s Island Park, in New York City, meant to reference jazz and improvisation and a legendary 1938 concert held there, to Ruptured Silence: Racist Symbols and Signs (2015) a dance performance installation at the Center of Contemporary Art in Columbia, South Carolina, to SUBVERSE Un/seen (2019) at The George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center in Austin, where the artist supplemented his exhibition with a performance of the Afro-Brazilian martial art capoeira in an empty and abandoned pool behind the museum. Otitigbe had painted the pool in rhythmic patterns with which the dancers interacted. “We need to activate spaces that have been in disuse, particularly when there are so many communities that have been displaced,” said Carver Museum’s exhibit coordinator Carre Adams for Spectrum News 1. “Part of what we have to do is preserve Black culture and history and aesthetic expression.”

Otitigbe’s latest project, Peaceful Journey, results from a contest held by ArtsWestchester, a nonprofit for the arts in that New York county. Earlier in 2020, Otitigbe’s design won the commission for a monumental sculpture in honor of hip-hop star Heavy D, who hailed from Mt. Vernon, New York. “I wanted to pay homage to the Mt. Vernon community that had such an important place in hip-hop with this work of art,” the artist said earlier this past fall, explaining that he named the sculpture after the rap artist’s song because it “offers a thoughtful and complex picture of the lives of Black and Brown people [living] in places like Mount Vernon, the Bronx, or Los Angeles.”

As he seeks a transformative experience throughout his career as an artist, he also looks to bring this spirit of transformation to his teaching. Otitigbe, who joined the faculty in 2018 as the head of sculpture, came with a B.S. in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an M.S. in engineering product design from Stanford University, underpinning his master of fine arts degree work. This year Otitigbe is serving as co-chair for the M.F.A. program alongside Professor Derrick Adams.

“My experience as a student may have been very different than those who are at Brooklyn College,” he says. “There were amazing resources at M.I.T. and Stanford, but the student body was not very diverse. I wanted that very much as a student. I live in Flatbush, and I am excited about the diversity in my neighborhood and on campus, and to be part of the vast City University of New York system, with so many amazing scholars.”

“A transformative experience—what the college seeks to offer is one that I also value,” says Otitigbe. To accomplish that, he has created new courses, including design thinking, soft sculpture, public art, and interactive art. “We’ve also started purchasing new equipment and tools, and even though the pandemic has prevented my work in person with our students, I am encouraging them to go out to look at exhibits and research art online. I want to help them, through their art, be storytellers, innovators, and visionaries. I want, for myself, to be a part of the long history of influential New York artists on the Brooklyn College Art Department’s faculty.”

An aerial view of the University of Virginia campus shows the Memorial to Enslaved Laborer’s concentric circles, creating what artist Eto Otitigbe calls a type of basin—the reverse of the rotunda on nearby Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s plantation home. A walkway points north and away from the site, representing the path that the enslaved of the South took to freedom. Photo by and courtesy of Sanjay Suchak.

Says Eto Otitigbe of the Memorial to Enslaved Workers at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, “We worked to create a space to heal, or protest, a space where change can always be facilitated.” Here, local healthcare workers have gathered to honor the many enslaved who toiled, unknown and forgotten, on those grounds. Photo by and courtesy of Sanjay Suchak

Nari Ward ’92 M.F.A.

Nari Ward

“I came to Brooklyn College by accident, you might say,” states Nari Ward ’92 about his tenure as a graduate student there. He had just received his B.F.A. from Hunter College (CUNY). “I had come to see Professor William T. Williams in the Art Department to get a letter of recommendation for another university I was applying to. Professor Williams asked me, `What about Brooklyn College?’ I had graduated from Hunter, and was thinking about a different experience from the city colleges. I told him I’d think about it. He pressed me. I was trying to get out of the door when he said, ‘Come with me,’ and took me to the Art Department, which was right around the corner from his classroom. He said, ‘I want this guy enrolled.’ The sculptor Lee Bontecue was on the faculty, as was painter and printmaker Allan D’Arcangelo. Professor Williams was always generous with his time.”

The Jamaican-born artist, who is today a professor of studio art at Hunter College, credits the mentorship of Williams and other artists of color, such as abstract expressionist painter Al Loving.

“Back then, the artists of color weren’t in the galleries, but they were around. You’d meet them mostly in residency programs. Al had had a studio on 42nd Street in 1989. One of his collectors was his landlord. He stayed at this big empty building. He was always so open to young artists helping him work. In fact, Al’s the one who told me I had to get William T. Williams to write a letter of recommendation for me.”

Gatekeepers and Curators

Ward says that it was not the lack of Black artists, but the fact that the curators and gatekeepers of the galleries and big arts institutions were almost exclusively White. “You had the show Harlem on My Mind in 1969, which was a disaster,” says Ward, referencing an exhibition that was meant to highlight the history of Harlem since 1900. “There were no African-American artists in the show. The curation was myopic. Art was a White, male- dominated arena,” says Ward, his sentiment most aptly summarized by a quote from Patti Astor, a New York City actor and part of the East Village underground and hip-hop scene of the 1980s: “The art world was white walls, White people, and white wine.”

Certainly, there were noted artists of color, such as Brooklyn College Professor Emeritus William T. Williams, and his Whitney Biennial peers—Romare Bearden, Sam Gilliam, Jacob Lawrence, and Jack Whitten—in private collections and museums. “But even Basquiat was considered somewhat of a fad when he came on the scene in the early Eighties,” Ward says of the Haitian American painter Jean-Michel-Basquiat, whose fame was initially fueled by the zeitgeist of the go-go Eighties, graffiti culture, and art as commerce. “Our own folks were not involved; there weren’t many collectors of colors.”

After graduating with a master’s degree in fine arts in 1993, Ward had work featured in the 45th Venice Biennale Cardinal Points of Art and the 1995 Whitney Biennial. He has gone on to have solo shows at the Contemporary Arts Museum—Houston, the New Museum in New York, Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, among others. His work has appeared in exhibitions from Spanish Harlem (UPTOWN: nasty women/bad hombres, El Museo del Barrio, New York, 2017) to Milan, Italy (The Great Mother, the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Palazzo Reale, 2015, and the mothership for many artists of color, The Studio Museum in Harlem (Passages: Contemporary Art in Transition, and The Listening Sky).

For Ward, there is more than a glimmer of hope when it comes to diversifying. “Institutions are realizing they have to honor their constituents, including those of color. The educational branch of the art world needs to be enhanced and broadened, bringing in diverse languages and diverse visions. A real sea change happens when institutions in the mainstream art world are accountable to the community they are serving, the neighborhood they are in, not just the one percent.”

Still, responsibility does not lie with artists, but the institutions they rely on. “It’s about creating discourse and also allowing for the pedagogy bar to be raised on that. The biggest failure of these institutions is that they are playing catch-up to what’s going on now. The fiction of the museum as a space of progressive thinking—what is their role? Cultural diplomats are what they should be trying for, to say this is a space to talk about these difficult issues. That racism is a human rights problem. And how do we take on White supremacy without putting off funders and trustees?

“I’m curious to see where the Black Lives Matter movement ends up. Corporate America has already diluted it. But what is new is that we have a whole new generation taking on the notion of valuing Black life.”

NARI WARD Amazing Grace. The installation arose from Ward’s 1993 residency at The Studio Museum in Harlem in response to the AIDS crisis and drug epidemic of the early 1990s. Ward bound more than 365 baby strollers with twisted fire hoses in an abandoned fire station in Harlem. On repeat was a recording of gospel singer Mahalia Jackson’s Amazing Grace. Ward’s work investigates themes that are informed by the locations and found materials in the communities in which he creates. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and London

NARI WARD Crusader, 2005. Plastic bags, metal, shopping cart, trophy elements, bitumen, chandelier, and plastic containers 110 x 51 x 52 inches. Installation view of We the People. Says Ward, “I attempted to bring dignity to the idea of the shopping cart as home for those without permanent residences, by transforming plastic bags filled with cloth into a membrane of protection.” Photo by Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and London

NARI WARD Scapegoat, 2018. Installation view, Art Omi, Sculpture and Architecture Park, Ghent, New York. Also part of an installation called G.O.A.T., Again in Socrates Sculpture Park Long Island City, New York. This giant, fake stone head is reminiscent of masculine historical figures, but matched with the long “hobby horse” stick and terminating in a rusty wheel, the sculpture is infantilized. Ward calls it a “mischievous piece” that references masculinity and monuments in a satirical way. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and London

Chloë Bass ’11 M.F.A.

Chloë Bass

“How did I get to Brooklyn College? On the B44 bus. I’m a native New Yorker,” says multiform conceptual artist Chloë Bass, laughing. “I went to Hunter for the pre-K through 12 program and left the CUNY system for Yale in part because we were encouraged to go outside of CUNY. I had some pretty mixed experiences my first time in a private school, so I knew that if I was going to earn a master’s degree that it would be in the public-school system.”

The 2008 recession arrived and Bass lost her job because of layoffs, so she decided it was a good time to go to grad school. “Because I did theater studies at Yale, the PIMA (Performance and Interactive Media Arts) program at Brooklyn fit. It was unique,” she says, and it jibed with her work as a multiform conceptual artist who creates, through “performance, situation, conversation, publication, and installation,” as she describes it. After graduating in 2011, she taught as an adjunct at the college for a year. “I have remained engaged through the larger PIMA network, which is full of really thoughtful, really political, really kind and interesting people.

Engaging in the World Around Her

“I’m the daughter of an artist. My mom is a Black immigrant artist from Trinidad who attended Cooper Union,” says Bass. “Because my mom was an artist, but an immigrant, and was successful, but struggling in a lot of ways that are just normal to Black women, I never really got the impression that artists were people who were supposed to be sequestered from society, which I think is a really common stereotype or myth. I lived with an artist; she was my mom. For me, what came first was not the work. It was the engagement with the world around me. My work started to form itself in response to that, gradually over time.”

Bass uses the daily life she speaks of as a locus of research into intimacy, from small scale, zeroing in on the individual in The Bureau of Self-Recognition (2011-2013); on pairs in The Book of Everyday Instruction (2015-2017), and immediate families in Obligation To Others Holds Me in My Place (2018–2022).

Moving forward in her exploration of patterns of human intimacy, Bass was commissioned to create an outdoor exhibition for The Studio Museum in Harlem. The 24 sculptures placed strategically in nearby St. Nicholas Park took the participant on a journey of self-reflection in a very public space. Yet, the intimacy remained in questions posted on billboards: How much of care is patience? How much of life is coping? How much of love is attention? Wayfinding, which remained open for a year, beginning in September 2019 (“We were lucky that it was an outdoor installation so that people could come even during the pandemic”), included an audio component.

“One of the things about the piece, especially the audio, is the meta-narrative to all the signs,” says Bass. “You don’t have to listen to it to feel something when you see the installation, but if you listen to it, you’ll have a very different impression of what the work is or does.”

Part of Bass’ inspiration for the piece was research she was doing on Alzheimer’s and dementia, what she calls “endless changing skylines in cities as a result of gentrification.”

“My grandma passed away in 2018, and I watched, at the end of her life, the way she was living in Manhattan. She lived in a neighborhood she was super familiar with, but she was also not familiar with herself anymore, mentally. I also noticed how the construction of so many glass towers was disorienting for her because she couldn’t figure out where she was. The way of navigating by way of familiar landscapes was slipping away. So it’s not just that gentrification produces economic-based displacement, but this emotional displacement that I think is not accounted for. The world being unjust produces emotional instability within us.”

Bass, who is now installing Wayfinding in St. Louis, where she has moved temporarily, was surprised that The Studio Museum reached out to her, and it had to do with the question that many artists of color continue to debate: What is Black art? “I went there all the time as a kid,” she says. “I saw great art that has been really informative to me as a person. But I have never made that type of art that I was seeing there.”

Bass goes further. “I did not think that an institution like The Studio Museum would actually grapple with a person like me, because I was not making figurative paintings or sculpture. There has been a switch that there is now a greater acceptance of what Black art is and isn’t.”

CHLOË BASS Wayfinding, St. Nicholas Park, Harlem, New York, 2019. Photo courtesy of the Studio Museum in Harlem (image credit: SaVonne Anderson)

Return to the BC Magazine